Front-end or Back-end Corporatization in Southeast Asia?

The rapidly evolving landscape for the SMEs of ASEAN

This is the first edition of Emerging, a weekly newsletter that explores the intersection of Tech and Finance in Emerging Asia. While existing coverage is broad, Emerging is for those who want to go deep. I’m hoping this newsletter can help quench the thirst for readers who want to peel-back another layer of the onion…

Welcome to ground zero of Emerging.

In this edition, we explore:

An introduction to Front-end and Back-end Corporatization and the impact of COVID on ASEAN’s SMEs

The rise of aggregators in Southeast Asia & the economics of different levels of aggregation: global, regional / national, and hyper-local

The inverse economic relationship between aggregators and suppliers depending on the level of aggregation

The long-term implications of COVID on the region’s economic make-up and contribution from SMEs

*Please note views expressed are strictly my own and not affiliated with any institutions*

Front-end or Back-end Corporatization in Southeast Asia

In general, larger companies are better positioned to weather downturns. They typically have more cash, better access to financing, more flexible labor costs and generally maintain more diversified income streams. SMEs on the other hand, have a more limited means of tapping the benefits of stimulus, limited cash reserves / financing access, and are more exposed to acute downturns - in particular the massive decline in aggregate offline demand posed by a pandemic. This, along with the divergence in digital capabilities, appears to account for a large portion of the bifurcation between main street and wall street; between a global equities recovery and the struggling underlying economy in our new COVID world.

Byrne Hobart - writer of The Diff - highlights the dichotomy in the U.S. with two possible paths forward for SMEs.

The pessimistic (long-term possibility) is front-end corporatization: small businesses just evaporate, their real estate is taken over by big companies, and (some of) their employees find new jobs at these companies… it wrecks the balance sheets of small business owners and their employees, dissolves institutional capital, and generally represents a lot of waste…

The optimistic view is back-end corporatization: that software companies and lenders launch an all-out sprint to modernize and recapitalize US small businesses, applying the scale advantage of big companies to solving the problems of local ones. In that happier outcome, small companies hang on for dear life, and come back leaner and ready to fight.

A similar battle will be fought in geographies around the globe with different stages of technological adoption and economic maturity providing varying backdrops & probabilities in this global tug-of-war.

COVID in ASEAN

Some trends in the digitization of ASEAN are easier to spot than others. Long-term acceleration in digital penetration of certain consumer segments - like eCommerce, online education, healthtech, and gaming - seems fairly obvious in light of COVID. These categories were already seeing strong increases in online penetration over the last ~2 years in particular, and COVID will only accelerate the curve. The real question is by how much? A question we will explore in the near future.

However, the more pressing issue for ASEAN is the impact to the region’s SMEs.

As exciting as tech companies are, the SEA internet economy is a fraction of the ASEAN economy - Vietnam topping the pack at just ~6% contribution in terms of GDP:

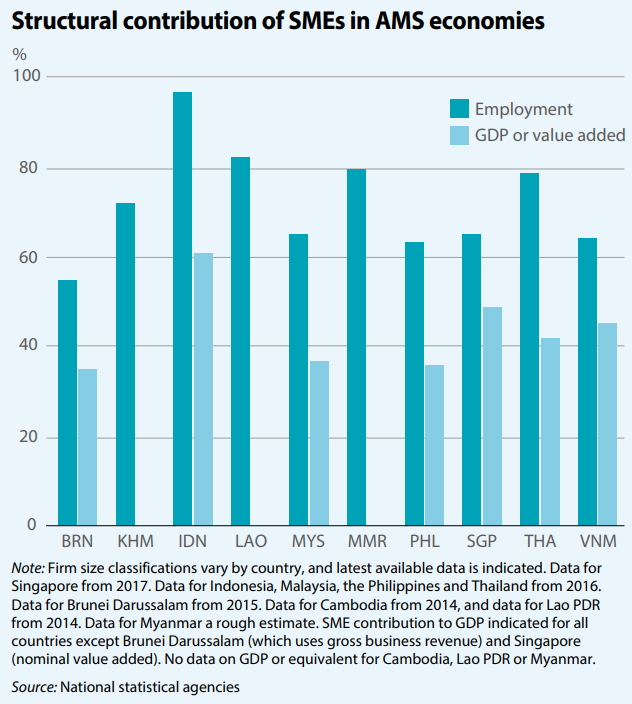

On the other hand, the region’s SMEs are essential - responsible for as much as ~97% of employment in the region’s largest economy Indonesia:

There is no question that the COVID pandemic ravaging the globe poses a particularly acute threat to SMEs globally. Even relatively wealthy countries like the U.S. are seeing tremendous economic stress: 33 million Americans have now filed for unemployment - many small business owners - and rates of unemployment are higher than any time since the Great Depression - (15%+ and rising).

While the U.S. was able to stem the tied of financial contagion with a US$2T+ “Bazooka” stimulus package, the economic tool kit for policy makers in developing economies is sparser. Many do not have the luxury of reserve currency status, have more precarious balance sheets and have a tendency to suffer capital flight in tough times - leaving them relatively few monetary, fiscal, and social tools to prop up the economy. SMEs - from the warungs of Indonesia to the sari-saris of the Philippines - with limited access to financing or tools to push online, are likely to have a particularly hard time making ends meet in a pandemic-stricken environment.

In the U.S., the economic contribution of SMEs is ~44% of GDP and ~48% of employment. In ASEAN, while the economic contribution by SMEs is similar, these less mature economies see significantly outsized employment contribution from SMEs. This would suggest the productivity of ASEAN SMEs on a per employee basis significantly underperforms their developed country peers in terms of GDP contribution of SMEs per employee vs larger companies. This adjusts for the differences between economic development.

Fortunately, the tools to help them compete are emerging and they have never been more important. They will also significantly re-shape the face of many economies.

Insert Big Tech - The Economics of Aggregation

Large consumer tech platforms have only really emerged as significant players within the ASEAN ecosystem within the last ~5 years. We can hash through the differences between platforms and aggregators in a later post, but for now assume their equivalence for simplicity.

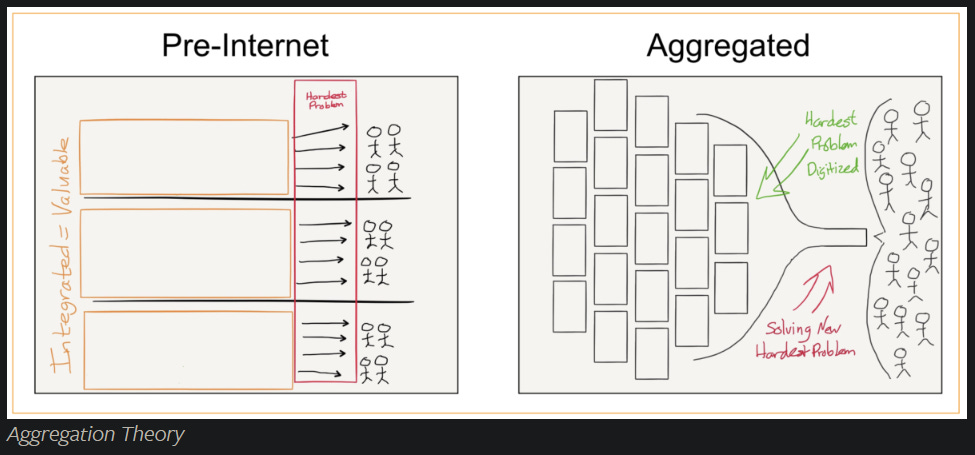

Aggregators - by definition - leverage internet connectivity to onboard smaller companies and consumers to match fragmented supply and demand. The goal is to onboard as many suppliers and customers onto the platform as possible into a self-reinforcing flywheel. The more consumers who join the platform, the more attractive for suppliers to join. The more supply on the platform, the greater selection available to the consumer. The concept is well illustrated by Ben Thompson below in his excellent blog Stratechery:

The interesting thing is that the level of aggregation matters and is different for different business models with different outcomes for the participants. Aggregators can be local, national or regional, or even global depending on the friction involved - the relevant physical barriers, different regulatory jurisdictions etc - in order to transact.

Purely digital aggregators like social networks or streaming services are not bound by physical barriers and have been increasingly able to implement global networks resulting in massive businesses - like Facebook or Linkedin or Netflix.

Others that are becoming digital - like payments - can build global businesses (Visa / Mastercard) but tend to run into more regulatory and integration friction so the ramp is much slower and can often fragment by region or country (AliPay / WeChat Pay, SEA eWallets etc).

Other aggregators, like eCommerce platforms - tend to breakdown at the national or regional level simply due to the constraints of the physical world. Shopee, Lazada, and Tokopedia’s matching of supply and demand requires substantial investment in not only internet connectivity, but a number of other enablers - both physical and digital - including storage, logistics and payments which tend to favor national or regional champions and proximity is important.

Other aggregators are more hyper-local in nature. They tend to be the most levered to offline SMEs - platforms like Grab, GoJek, Meituan-Dianping, DoorDash etc - that offer on demand services in ride-hailing, food delivery, or affiliate marketing to local establishments.

The networks in this last category are inherently more constrained in nature as they depend on local liquidity as opposed to regional level liquidity. If I want a ride on demand, I will generally only be interested if the wait time is under 7 minutes. If I’m a driver, I prefer not to drive 45 minutes for my next ride. If I’m a local restaurant owner, I’m only interested in marketing to consumers within a ~20 min delivery of me. However, if I’m a small seller of workout-at-home dumbells, empowered by a built-out logistics network, I could service anyone in the country - or even look into cross-boarder demand for my products.

Inverse Law of Aggregation

The power-law dynamics and therefore the economics of each of these levels of aggregation tends to have an inverse relationship between the platform and the sellers onboarded onto the platform. Hyper-local platforms levered to offline tend to have poorer economics because the cost to service the next marginal customer is not zero (unlike say Facebook), but also because the lack of broader network effects or aggregation-level limits the barriers to entry and invites more competition. The platform needs to fight for liquidity at the local level - going market by market - onboarding supply and demand and creating liquidity in each neighborhood or subsegment of the city. On the other hand, the eCommerce platform will onboard suppliers and customers and can match them nationally.

The outcome for the individual suppliers on each platform is subject to different economics due to the aggregation level of the platform. A musician on Spotify has global distribution, meaning anyone in the world can download the app and enjoy his/her music. However, this also means he/she has global competition. In a market of global liquidity, the competition is exceptionally intense. The very best are compensated handsomely while the vast majority struggle to be found. Welcome to the impact of digitization. However, the equation is largely inversely correlated for hyper-local platforms. While the competition at the platform level is intense - onboarding supply and demand - the competition on the supply side level is relatively more tame. Restaurants are notoriously cut-throat, but generally only have to compete in a given neighborhood. The level of competition for the AVERAGE seller on the platform - and the corresponding profit pool - scales up and down with the level of aggregation which largely depends on the business model & the real-world constraints.

Platforms - from Exciting to Essential Overnight

Forrest Li - founder of SEA - highlights the increasingly essential nature of platforms on the Q1 2020 earnings call:

Shopee is becoming a more integral part of the commercial ecosystem in each of our markets with consumers now relying on our platform for their stay-home daily essentials and other consumption needs. At the same time, more sellers are migrating to — or relying on Shopee to sustain and grow their business as our economies become more online and contactless, the digital payment and financial services that SeaMoney provides are becoming an ever more important part of the structure in our region.

The coronavirus crisis is driving a step change in the growth of the digital economy globally, particularly in the markets and the segments where we operate. It has materially accelerated a shift to online lifestyle that is broad, deep and, in our view irreversible.

This is exactly correct. Supplying smaller sellers with the tools to rapidly switch gears and sell online is literally saving livelihoods in this environment. Not just Shopee but all eCommerce platforms. Many other businesses - with more COVID resistant models like edtech and healthtech - are likely seeing similar tailwinds. I imagine the customer acqusition cost (CAC) on both the supply and demand side is dropping dramatically and the digital penetration is expanding aggressively in a shrinking market. Not only is eCommerce more essential, but being able to accept digital payments or market to local restaurant customers digitally went from a nice-to-have to a must-have overnight. While still very early, many more SMEs will begin experimenting with the tools than before, almost as an insurance mechanism to ensure they can reach customers in an omni-channel manner going forward.

Aggregators & the Corporatization of SMEs

What does this mean in a country like Indonesia with 97% of employment shouldered by SMEs? SMEs who are significantly less productive on a per employee basis in terms of economic contribution and output relative to developed markets? The good news is the various aggregators and enablers are providing the tools needed to survive, evolve, and compete more effectively with larger companies and adapt in a pandemic-stricken world:

Ecommerce platforms are allowing merchants to reach consumers online

GoJek and Grab allow restaurants to reach consumers in their homes

HaloDoc allows doctors to visit with patients without the dangers of in-person interaction

And so many more…

This is amazing and would suggest that Southeast Asia is heading down the more positive path - back-end corporatization - laid out by Bryne Hobart above. I think this is largely correct discounting for the more limited scale of adoption of tech platforms in ASEAN today. On net, the near-term economic pain will be significant, but the benefits of onboarding with a platform for omni-channel access to customers has never been more important and will enhance productivity for the region’s SMEs. This will accelerate the aggregation flywheel & potentially send SEA’s digital penetration on a trajectory closer to China’s (to be explored further in the future).

However, aggregators tend to have a funny way of sneaking out of the deal controlling the relationship with the end consumer. When a consumer looks for goods online, they don’t type-in the particular URL of an individual store - they type in Amazon.com or Alibaba or MercadoLibre or FlipKart. In the front-end vs. back-end corporatization debate, the two-sided aggregator starts to look a little more like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde:

Back-end corporatization between the SME and the aggregator, but front-end corporatization between the aggregator and the consumer.

The level of aggregation also matters - specifically in terms of employment and competition. With such a high level of contribution from SMEs in terms of employment, shifting online can expose them to increased levels of competition. This is less severe in hyper-local aggregators because competition is largely restricted by space and time, but in winner-take-all national level aggregators, many SMEs will struggle to keep up. The $ consumers spend will not change much, but their options are expanding dramatically to the infinite shelf space online. Similar to how other geographies have evolved, Productivity will go up. Consumers will be better off. But will the average SME be able to compete in a new digital economy with a power-law distribution?

Time will tell.