Precision Monetary Policy

Empires & Money, US-China Tensions, and Why DCEP Matters

Durian’s weekly thought to Ponder: “What will be the world’s reserve currency in 2050? If your answer is not the USD, what does that mean for your current portfolio?”

Morning all,

Welcome back to Emerging - a publication going deep at the intersection of tech & finance in Emerging Asia. Brief note: I noticed we had a lot of new sign-ups in Southeast Asia this past week, so wanted to direct new joiners to last week’s Ecommerce in LegoLand (on modular vs integrated eCommerce stacks) or the popular Front-end or Back-end Corporatization in Southeast Asia? if they are looking for more regionally-focused content which will continue in the coming weeks. However, this week, we are zooming back out. (download the graphs - worth it)

This week, we explore:

Empires & Money: the archetypal rise and decline of civilizations through time

Reserve Currency Status - The US and money printing’s double-edged sword

From precision medicine to precision monetary policy

The blunt tools of stimulus, the negative monetary cycle, and why the DCEP matters

I feel like the DCEP - China’s new “digital currency electronic payment” initiative - should get more love. Relative to the usual headline suspects - “trade war”, “tech decoupling”, “TSMC & the Taiwan Question”, “Rising tensions in the South China Sea” - the DCEP has flown surprisingly under the radar.

Western audiences hardly know about it.

Chinese consumers don’t see much benefit beyond the WeChat Pay & AliPay UX.

Crypto-enthusiasts mock it as a co-opted bastard of the coming decentralized utopia.

EU ministers are busy simply keeping their existing monetary union afloat.

And American policy makers seem perfectly happy with the fractional banking status quo; testing the limits of reserve currency status via ever-larger stimulus injections to a point where onlookers can be forgiven for thinking U.S. policy makers may actually believe Modern Monetary Theory.

Meanwhile, earlier this year, Chinese officials have begun quietly rolling out DCEP pilots to little fanfare. I think this is one of the more underrated stories of the “new Cold War”.

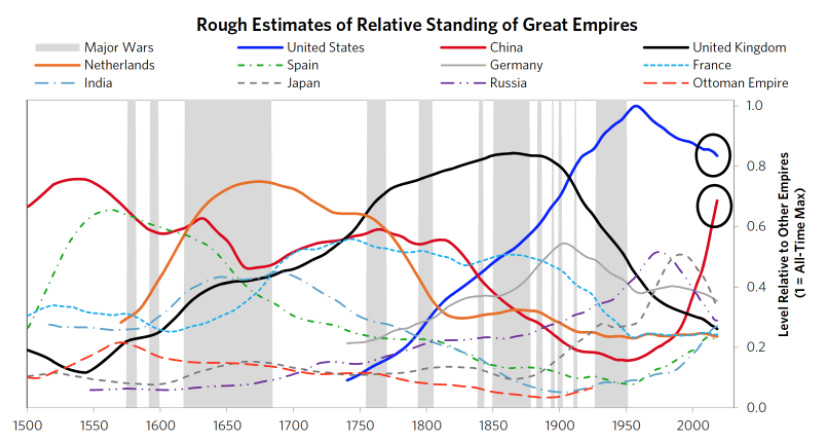

Setting the Stage - Empires & Money

Over the weekend, I had the pleasure of catching up on Ray Dalio’s Changing World Order series which I lean on heavily below to set the context. It is absolutely worth the read with the caveat it is as long-winded as it is excellent. The series explores the rise and decline of empires based on a combination of cultural, geopolitical and monetary cycles. The standard archetype below typically takes place over ~200 years:

The simplified cycle above can be further broken down into core factors which serve as leading and lagging indicators for each country’s maturity within the cycle:

A general staggering across factors is apparent:

Rising education is clearly the leading indicator of an Empire’s rise

Better education leads to innovation, tech, and increasing competitiveness

Innovation & competitiveness = increased output = increased trade = increased military presence to protect its increasing trade

Increasing output and trade leads to deeper financial markets as recycled capital is pooled for ever more ambitious expansions

Finally, the lagging indicator is reserve currency status. As a country becomes dominant in terms of trade, it’s currency will be used more in global transactions and other countries will seek to invest in its deepening capital markets - which are likely stable and protected by a strong military. This wide-spread adoption provides the super-power with a near infinite ability to borrow and spend.

Based on Ray’s analysis of these eight factors, the current stage of global power cycles looks like this:

The US is still on top but is stagnating. China, on the other hand, is rising fast. When mapping out the U.S. by factor, we see the divergence between tech & financial supremacy vs. a relative decline in education and economic competitiveness since the post WWII era.

Interestingly, much of the United States relative decline is of its own making. Initiatives including the Marshall Plan and GARIOA grants provided unprecedented capital injections to rebuild Europe and Japan post WWII. The liberal world order promoting free markets was a key facilitator of Asia’s rise on the back of foreign direct investments and exports to fuel the American consumption engine. This rise included China - which began “opening up” under Deng Xiaoping in the 80s, accelerated through the 90s, and reached escape velocity after the U.S. granted entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. While good from a humanitarian lens, many of these policies accelerated the US’s relative decline in trade and competitiveness and led to a less healthy balance sheet.

What remains in 2020 is supremacy in tech, traditional military factors, depth of financial markets - and potentially the most powerful - reserve currency status.

Reserve Currency Status - a double-edged sword

Reserve currency status may be one of the most important advantages granted to an empire. In Dalio’s own words:

Countries that have the world’s reserve currencies have amazing power—a reserve currency is probably the most important power to have, even more than military power. That is because when a country has a reserve currency it can print money and borrow money to spend as it sees fit, the way the US is doing now, while those that don’t have reserve currencies have to get the money and credit that they need (which is denominated in the world’s reserve currency) to transact and save in it.

Clearly, the US dollar is today’s reserve currency. The US dollar accounts for ~55% of the world’s international transactions, savings, and borrowings compared to just 25% for the Euro, 10% for the Japanese Yen, and just 2% for China’s RMB. Incrementally, the US accounts for just 20% of global GDP but makes up close to 60% of central bank reserves globally.

Many crises - such as wars, pandemics, depression, or inequality - can be more easily assuaged with reserve currency status. Wars can be more easily financed. The deflationary impacts of pandemics and depressions can be met by continued stimulus. The country can more easily finance robust welfare programs. The debt to owed to foreign holders can be reduced simply through increasing the money supply under ones own control.

A very powerful advantage.

Clearly the American government will yield this power to the benefit of the American people - more power to combat deflationary cycles, plug liquidity holes, and combat economic shocks - while foreign nations receive very little. In fact, this luxury comes at the expense of foreign governments who hold large USD reserves financing the U.S.’ mounting expenditures. Other countries have much more limited flexibility in the face of a debt crisis because many of their debts will come due in USD.

While reserve currency status is extremely hard to displace, it does not last forever. The flexibility afforded also makes it easy for an Empire to over-spend. Over time, chronic over-expenditure and irresponsible monetary policy erodes trust in the reserve currency as borrowers see debt-loads mounting and the easiest political path (more printing vs. austerity) likely to reduce the value of their reserves in real terms.

While the U.S. continues its profligate spending, as I highlighted in Monopoly Money (most popular post to date…), fiscal irresponsibility is relative:

Despite poor fiscal and monetary practices, near-zero interest rates, and an increasingly ailing balance sheet, demand for USD and treasuries remains strong. There is simply nowhere else to go.

Japan has been stagnating since the 90s with a Debt / GDP ratio of ~230%. The European Union is following suit and the very existence of the monetary union in question. There is a high probability the Euro doesn’t see 2030. The sterling is a relic from a colonial past and is rapidly being weaned from reserves. While China has a healthier government balance sheet, there are strict capital controls for a reason. It’s doubtful China will rapidly open its financial boarders after the strong outflow pressures witnessed in 2015 and 2016. The rule of law is still too arbitrary.

That leaves…. the U.S.

However, a chronic deflationary environment since the global financial crisis of 2008 combatted by unprecedented quantitative easing (QE), followed by Trumps tax custs, followed by US$4 trillion in stimulus to fight the economic effects of COVID is… starting to push the envelope.

Precision Medicine

The analogy is apt. Recently, the medical community has seen a shift towards a combination of preventive care and precision medicine. As opposed to waiting for patients to get sick and then reacting, the new, more cost-effective paradigm, aims to keep patients healthy and avoid financially draining chronic illnesses. When a patient does get sick, precision medicine aims to tailor treatments by subgroups of patients instead of a “one-drug-fits-all” model.

Central Banks need precision monetary policy.

When it comes to monetary policy, central banks today are left with relatively blunt tools - a “one-drug-fits-all” approach if you will. Similar to drugs, these tools have diminishing returns with continued use and can turn toxic past certain thresholds:

The first line of defense is interest rates. By lowering rates, governments encourage spending by making borrowing more affordable. Unfortunately, interest rates are currently zero or negative in most “developed” nations

The second line of defense is quantitative easing - government borrowing to inject the banking system with capital to plug liquidity holes or avoid a deflationary cycle

The third is helicopter money - simply increasing the money supply without a corresponding obligation. This is dangerous and has historically been correlated with hyper-inflation if done in excess.

Unfortunately, the level of customization provided by these tools is limited and is contributing to the dangerous cycle painted in broad strokes below:

The Cycle: much of the developed world has been in a low-growth, deflationary environment since the Global Financial Crisis. To stimulate the economy, governments and central banks have resorted to unprecedented quantitative easing to combat deflation. This untailored stimulus floods the financial system to encourage spending but has generally not trickled down to everyday consumption use cases (CPI inflation persistently below 2% targets). Instead, the inflation goes into asset prices (NASDAQ near all time highs in a pandemic). Banks are hesitant to lend to individuals and SMBs in a crisis, but corporations capitalize on free credit to expand and buy back stock. Individuals with stock ownership benefit as more capital flows into what seems like the last remaining asset class with real yield and the wealth gap expands further - sowing more political strife. The shrinking middle-class consumption further slows growth requiring a higher dose of stimulus to encourage spending and fight deflation. And around we go.

As debt loads and money printing continue to increase, foreign governments will begin to question if their US and Euro denominated reserves are in fact a good store of value. As this cycle continues, the very privilege of reserve currency status will come into question.

This negative spiral is why the DCEP matters.

Why the DCEP matters?

The DCEP is a forward-thinking tool from the Chinese government to centralize control of monetary policy. Instead of relying on legacy banking systems which may or may not get capital to where it needs to go, why not go direct now that the tech exists? Are there risks with disintermediating aspects of the banking system? Sure, which is why it will be phased in slowly and integrate with many incumbents. Are there privacy / control trade offs every country would need to balance to make it work for its society? Clearly.

However, I’m surprised its not being explored with more vigor.

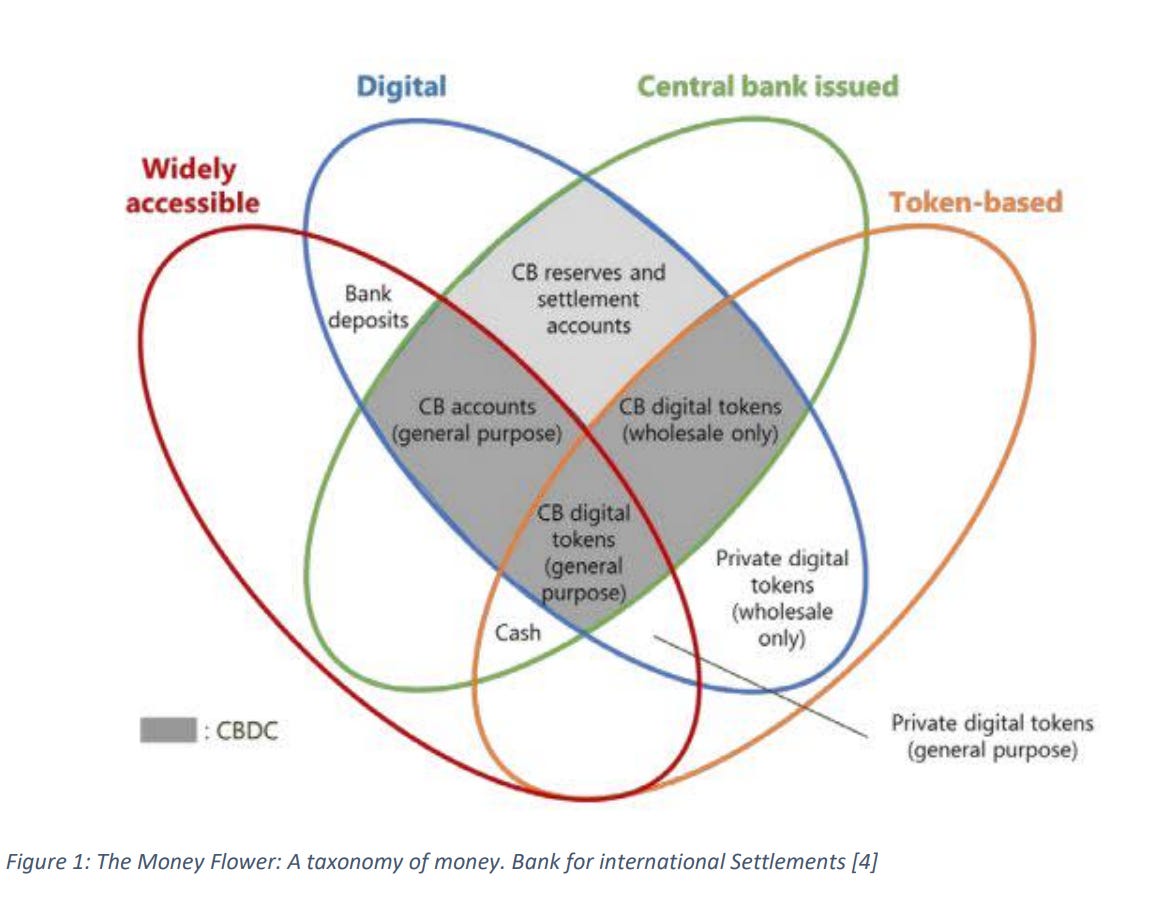

The below “money flower” from the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (I know, I read the most exciting stuff) illustrates how Central Bank Digital Currencies (“CBDCs”) compare with other types of money compared by:

1) Issuer (central bank or other)

2) Form (digital or physical)

3) Accessibility (widely or restricted) and

4) Technology - token or account-based (cash and many digital currencies are token-based, while balances in reserve accounts and commercial bank money are account-based)

Several people have asked me why China needs a CB digital currency at all given its consumers and merchants already have access to world class digital payments in AliPay and WeChat Pay? The answer: its not for the consumers or merchants. In reality, the DCEP may have slightly lower fees, but will have a hard time matching the UX of leading private platforms. I suspect it will just integrate with them for distribution. The real answer is monetary policy.

Aside from more optimizing potential advantages like:

Ensuring the public has access to legal tender as cash becomes less available

Faster settlement / extended settlement hours, reduce expensive coinage

Improving counterparty credit risk for cross-border interbank payments and settlements, etc

The real advantages are the enablement of more tailored monetary policy:

To retain control - if private eMoney solutions get too much adoption, the government has less control and can weaken the transmission of monetary policy

Less commercial risk - commercial banks are not fully backed by reserves (fractional). The GFC proved they are not always responsible actors.

Direct - An interest-bearing CBDC could make monetary policy more effective as the pass through of interest rate changes by the central bank would be more direct relative to bank deposits who independently set rates.

And tailored, programmable money:

Precision Stimulus - look at how hard it was for the US government to get money to citizens in the pandemic on legacy infrastructure. A widely adopted CBDC would allow for instant transfer of funds to qualified individuals and businesses which could be more tailored by need as opposed to “flooding the system” with trillions which contributes to the negative cycle and political turmoil outlined above.

Programmable Incentives - this is weird, but what if certain distributions were programmed to “disappear” if they were not spent on consumer goods within two weeks? Use your imagination - novel incentives could encourage consumption where and when it is must needed to spur localized inflation

Surgical monetary policy is why the DCEP matters. And that is why governments around the world should be paying attention.

If the U.S. government is serious about retaining one of its most important advantages - reserve currency status - it will need to be more surgical in its approach to monetary policy going forward.

With the Asian Financial Crisis still in the rearview mirror, policy-makers of Emerging Asia should be even more keen to fast follow. Without the luxury of reserve currency status, emerging nations have a more precarious needle to thread. When all of your debts are in a foreign currency, exacting monetary management is essential.

Enabled with new tools for precision monetary policy, perhaps Emerging Asian leaders can save their people a lot of pain.

***

Emerging is a newsletter going deep at the intersection of tech & finance in Emerging Asia. Subscriptions are free & delivered to your inbox most weeks. Prior musings can be found here.